“My dream for orangutans is that the people near the forest act as their guardians” – Sari Fitriani didn’t set out to become an activist. She just thought a career that involved commuting in her native Jakarta’s traffic seemed humdrum.

“Yeah, I’m kind of like that,” she laughed. Fitriani wanted to travel to the parts of Indonesia only rich tourists could afford to see.

So, after finishing up her physics degree from the Institut Teknologi Bandung, she applied to an energy service program and packed her bags for the Mentawai Islands, some seventy formations that hug the coast of West Sumatra.

In her job, Fitriani oversaw the construction of solar energy panels to be sustained by the local communities.

She was amazed at how different the atmosphere was from her home city. There were no traffic signals, and most people didn’t speak the national Bahasa language.

Unlike the majority Muslim Jakarta, almost all of the people in the villages were Christian and had completely different customs.

To become an active member of the community, Fitriani learned the local tongue and attended religious services.

By the end of her eight-month term, Fitriani knew she wanted to keep exploring her bio- and demographically diverse nation.

She enrolled in a similar service program in East Kalimantan and lived in the Merasa village for a year. It was there that she met the founder of the Centre for Orangutan Protection.

The Centre for Orangutan Protection educates local communities about the critically endangered native ape and fights to preserve the creature’s natural habitat by exposing and helping to prosecute illegal deforestation activity.

The organization also has a rehabilitation facility for injured and orphaned orangutans, who are often victims of poaching, black market trading, and palm oil plantations destroying their homes.

Fitriani was drawn to the centre because it aims to help the local people and forests live in harmony, and she thought caring about orangutans’ environment could, in turn, empower the natives to protect their homes from corporations.

Indonesia’s biodiversity, which includes the world’s third-largest rainforest, faces an alarming confluence of threats.

The country’s widespread forest fires, legal and illegal logging, mining, and unsustainable agriculture including palm oil harvesting account for a third of the world’s carbon emissions from deforestation and land degradation.

Local species are hurting as a result. Last year in 2019, the Sumatran rhino went extinct, and there are only around 120,000 orangutans left in the wild, with their numbers continuing to dwindle.

Palm oil is a major cause of the orangutans’ plight. Indonesia is the largest producer of the substance in the world, bringing billions of dollars into the national economy.

Palm oil is found in everything from lipstick to cookies, and can only be grown after the local flora and fauna, including where the orangutans live, are razed to the ground.

Some companies and nonprofits are working to make palm oil harvesting more sustainable, however, by prohibiting the clearing of primary forest land, reducing greenhouse gas emissions, and protecting the welfare of the local people and wildlife.

One of Fitriani’s most recent projects for the Centre for Orangutan Protection involved assessing deforestation in the Leuser Ecosystem, a 2.6 million hectare-expanse considered to be one of the most important remaining forests in Southeast Asia.

While the area is technically protected under Indonesian law, illegal development continues to take place.

Fitriani and the organization are also eagerly awaiting an ecosystem restoration concession license.

Started by the Indonesian government in 2004, the concession program grants companies 60-year ownership of a piece of land for the purpose of restoring it to its natural habitat and empowering local and indigenous communities.

So far, around 575,000 hectares have been awarded out of the 2.3 million reserved for these licenses.

Once the concession is granted, the Centre for Orangutan Protection plans to use the allotted space to release rehabilitated orangutans back into the wild.

Seeing the apes go home to the forest is “the most heartwarming feeling,” said Fitriani. “Some of them cannot even peel a banana the first time they enter our rehabilitation centre.”

Her colleagues teach the orangutans everything from making nests to swinging and climbing from trees.

Once the so-called men of the forest [Oragutans] are deemed self-sufficient, they are brought to their natural environment in a cage, and a small ceremony is performed before the animals are finally released, free to explore their new surroundings.

Many, however, seem unwilling to leave their caretakers’ sides. The last part of the process isn’t what you’d expect, said Fitriani.

“In the movies, it’s kind of romantic when the released animals come back to the people, right?” she said. “But in reality, it would be so much better if they just went away.”

The humans often have to run and hide from their counterparts to ensure that the red-haired apes can swing life out on their own.

Fitriani plans to spend the rest of her career protecting orangutans, the environment, and Indonesia’s indigenous populations.

She wants to earn a master’s or PhD in sustainability with the goal of helping to create national policies around the native apes and sustainable development.

“My dream for orangutans is that the people near the forest act as their guardians,” said Fitriani. “Not the foreigner people from another country or people from Jakarta, but the local people.”

Written By: Sarah D. Collins – a graduate student journalist at Columbia Journalism School.

Images Copyright – I Am New Generation Magazine | Sari Fitriani | Unsplash

More Stories

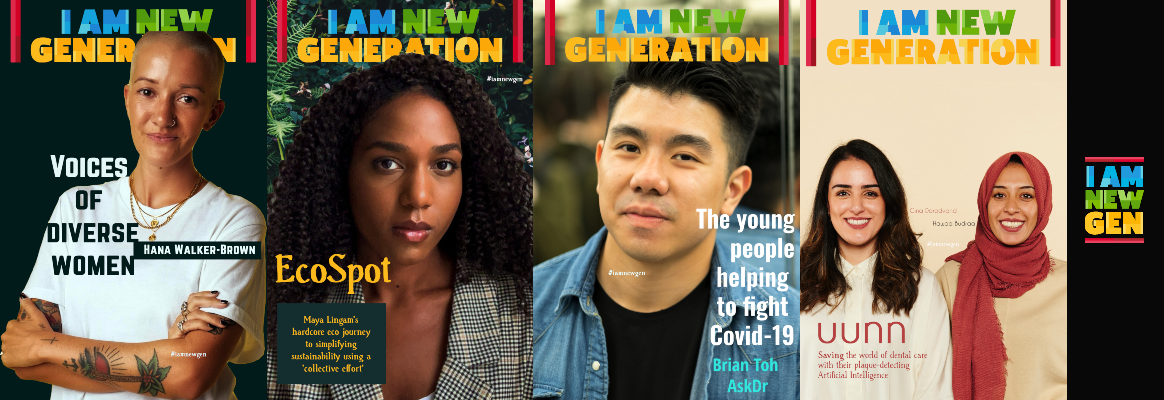

Voices of ‘diverse women’ – Why the world is ready!

Why being a ‘women of colour entrepreneur’ is a challenging business

‘We believe the day is near when all pharmaceutical needs of Africa shall be produced in Africa’